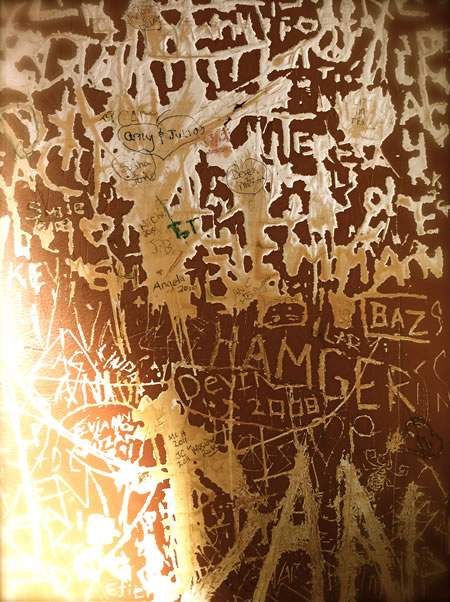

I was studying the different scratching on the surface of a wall — in a room that was covered with the graffito — Latin for “little scratching” — of hundreds of people.

Except that they didn’t only write on the wall, but incise their ideas deep into the plaster. That tradition, in a funky way, permeates the walls of

A couple of thousand years back, Herculaneum (and Pompeii) and other Roman cities, the graffiti was found in two ways: for one, scratched and incised in the walls and street ways; and in others, beautifully brush drawn, in styles that were popular for the announcement of gladiatorial fights, street and arena amusements, as well as complaints, love fools, drunks and alley cat observers.

Why not love, then? A graffito, Herculaneum:

Scripsit qui Voluit.

“Anyone who wanted to do so, wrote”

Alliget hic auras si quis obiurgat amantes et vetet assiduas currere fontis aquas.

“Anyone could as well stop the winds from blowing and the waters from flowing as stop lovers from loving.”

Seeing these walls, (right now) and two thousand years back, I was contemplating — the markings of the hand. In this way, these lines, even alphabetic are still are like little maps — a cartography of the way that they’ve, the scratchera, wandered. Looking at each one, a little scribbled clustering, I look into them, and immediately think about what way they have come, for why, where, and for which?

Why scribble here?

That writing, it goes back to the ancient way of the sign, the graph — which, in the old form of the word — was scratching. And in the beginning, that was the way of all writing: scratched, incised, rubbed, brushed and painted in the message

of then.

And I believe in the messaging

of now.

Reading, everything.

t | vancouver, british columbia

INNOVATION TEAM STRATEGIES

Girvin Cloudmind | http://bit.ly/eToSYp