Ancient wisdom recounted, savored and documented.

Several years ago, I’d been traveling on AirFrance, and reviewed an article about the careful restoration of an extraordinary grouping of manuscripts. Beautiful. So beautiful, that back then, I’d added some of the pages to my journals.

Timbuktu, Mali, is spectacularly remote:

Located in the center of what one might define as nothingness — still bounded by the grand curves of a major river, the Niger, a commerce portal, preserving its presence since the founding of the city in 1100 AD.

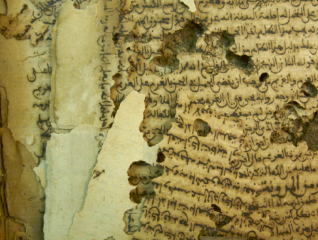

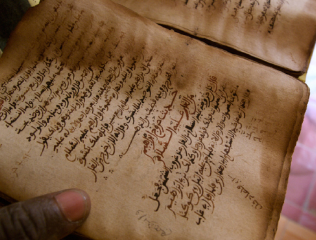

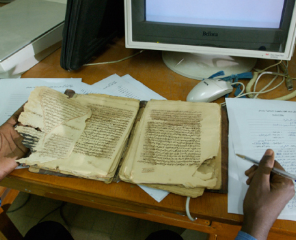

But decaying, the fragile texts were either being sold off, due to the monstrous implications of poverty, or were corroded by the action of insects, or less than appropriate care withering in the blistering heat of Mali.

According to Professor John O. Hunwick, “Efforts are now being made to preserve this literary heritage, beginning with some of the major collections of the city of Timbuktu.”

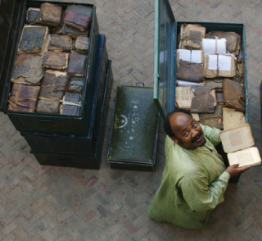

The actual number of manuscripts, in family collections, libraries and gathered “trunk cases” for protection is rather amazing — tens of thousands of books in various states of condition have been recovered, organized and are set for study and archiving.

Here’s a more scholarly and historical perspective, expanding on Hunwick’s historical reference — the full link is here: http://sociolingo.wordpress.com/

“The Niger Bend is to West Africa what the Nile Valley is to Egypt: an ecological life source and a civilizational magnet. Historically, the Niger also provided a great highway of communication across the region and provided a link between the lands of the desert and North Africa and the lands of the savannahs and forests in the South. The intensive and extensive human activity that has taken place in this region for thousands of years has left behind its traces in a large number of archaeological sites.

Over the past 600-700 years another legacy has developed: that of the literate culture of Islam symbolized by the extraordinary richness of private collections of Arabic manuscripts that still survive, often precariously, in the Niger valley and its desert hinterland. Timbuktu, located on the northern most bend of the River Niger in Mali, was a celebrated centre of Islamic learning from the fourteenth century onwards — local scholars wrote their own works and there is also evidence of a sophisticated local book copying industry in Timbuktu.

The historic city of Timbuktu, now the administrative centre of Mali’s Sixth Region, lies at a crucial point where the Sahara desert meets the river Niger. Its geographical setting made it a natural meeting point for settled African populations and nomadic Berber and Arab peoples. Founded around the year 1100 CE, it rapidly became a focal point for caravan commerce originating in North Africa or the Saharan oases. The city’s rapidly growing prosperity, soon attracted scholars to it from many quarters from Mediterranean Africa, from the Saharan oases and from West African towns such as Jenne and Walata.

By the mid-fifteenth century Timbuktu was as much a city of learning as it was a city of commerce. The scholars who settled there brought their libraries with them, and avidly purchased manuscript books imported from North Africa and Egypt. Leo Africanus remarked on the “numerous judges, scholars and priests [i.e. imams], all well paid by the king, who shows great respect to men of learningâ€, and added “Many manuscript books coming from Barbary are sold. Such sales are more profitable than any other goods.†By the fifteenth century, the city’s scholars were writing their own books for teaching purposes and to satisfy a demand for scholarly works in law, Qur’anic study, traditions of the Prophet Muhammad, theology, and Arabic language, and a more popular demand for pietistic literature and poetry in praise of the Prophet.

During the period of the Askiyas (or rulers) of the Songhay empire (1493-1591), there was considerable support for the Muslim scholars of the city, many of whom lived in the northern quarter around the celebrated Sankoré Mosque. Some received gifts from the rulers in cash and kind, and the renovation of the city’s mosques was underwritten by the state. One of the rulers, Askiya Dawud (who reigned 1549-83) is said to have established public libraries in his kingdom.

But the principal resource of Timbuktu scholarship lay in the private libraries of individual scholars and some of these libraries were evidently quite large. The celebrated scholar Ahmad Baba (d.1627), who was among those deported to Morocco in 1593 following the Moroccan conquest of Timbuktu and the Songhay empire, complained to the sultan of Morocco that his library of 1,600 books had been plundered, and his library, so he said, was one of the smaller in the city.

To this day the city still boasts some 60-80 private collections, the largest of which, the Mamma Haidara Memorial Library, http://www.sum.uio.no/ has been rehabilitated through a grant from the Mellon Foundation,

while a catalogue of its contents is being published by the Al-Furqan Islamic Foundation.

There is, as well, an active training program, bringing students together to learn the arts of translation, textual gathering, documentation and library science, to define the scale of the collections that are being studied.

The Fondo Kati Library http://www.sum.uio.no/ is now under construction with financing from the Spanish Gabinete del Consejero de Relaciones Institucionales. The contents of several other private collections were acquired by the Ahmad Baba Institute, a public institution that now contains over 18,000 manuscripts.

Aside from contributions by private organizations, family collections in Timbuktu, as well as UNESCO http://portal.unesco.org/ and Ford, the efforts continue, refreshed as recounted here http://www.scienceinafrica.co.za/ and Global Knowledge, http://siu.no/magazine/ the work continues in the translation, digital gathering and imagery of thousands of the books,

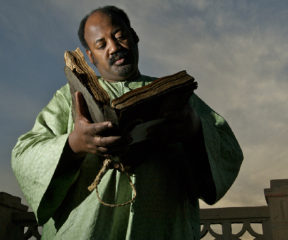

carrying on a tradition of centuries of learning — still, in many ways, practiced with the selfsame reliance of the Arabic text, memorization and perfection in practice.

And finally, as a kind of reverence to the heart of my personal experience and evolution as a designer — there is a return to the art of calligraphy, in reviving a nearly extinct practice, in the heart of the desert, in the center of Timbuktu.

What more do you know?

—-

Tim Girvin

Imagery from Ami Vitale unless otherwise noted. Other imagery undocumented.