The tree prints | 1979.

Girvins like trees. No, they love them.

Every member of our family has some connection with trees. And I suppose that arboreal love could have some distant simian link, like the notion that if you suddenly jerk when you are just dozing off, it’s a recollection of sleeping in trees.

I don’t know the reasons precisely why, but we love them. All kinds of them. And each of us has a special connection. I savor drawing them, photographing and being in them, forest spaces and climbing them, as well.

But mostly being in them. With them.

So when I ran into this reference in the NYTimes on a tour for the Land of the Giants (actually a ring of two states), I recalled these relationships — a love of trees. And I’ve decided to write 10 stories about them. To be posted at tim.girvin.com.

Jim Wilson | The New York Times

I’d recommend a contemplation.

And maybe a trip to the “land of the giants”, given that these are perhaps the oldest living entities on planet earth.

The magnetic presence of old forests is unmistakably powerful. And empowering. Being among them, you feel linked to living in a wholly different way. But they don’t have to be big-treed forests to be so emboldening in the link between your sentience in experience and the power of living things.

Smaller groves can be just as inspiring.

My father, George Girvin, I imagine, is the seed for the love of trees in our family. He’s been planting, and transplanting, and caring about forests for as long as I can remember. Our family has a farm southeast of the city in Spokane — once conventional fields of grain and grass are now given over to trees, mostly naturally dispersed. But many of the trees are planted. Our summer place at Lake Coeur d’Alene has a number of transplanted trees. My brother Jonathan has been tending to these trees over the last decade, in trips from his home in NYC, on break. My brother Robert has his own tree projects. Matt, my youngest brother, now passed, similarly affected a deep love of the arboreal — even bringing back seedlings from Mongolia — that are thriving in the hillocks of the Girvin farm. My mother simply loves to be around them — for us, my Mom and I, it was a favored respite going to the arboretum. And like looking for museums in other countries, I savor going to them — the tree parks.

I like to know the names of them. Where they come from, how old they are — what is their history? And, to a relationship with trees — I have mine: being among them, photographing them, drawing them. Climbing them.

So begins, then, a series on the tree. What does the spirit of them mean for me?

Since I’ve “drawn” my father into this, I’ll offer this opening story. My father had commissioned me to create series of 4, two-by-four feet plexiglas panels for his office.

About this time.

1979.

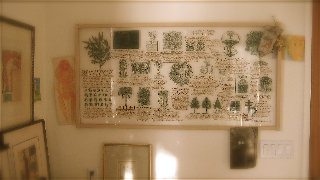

And this was the beginning of my career, as a calligrapher, illustrator, designer and storyteller. I made the actual screens for printing on the surfaces of the plexiglas by hand — writing and drawing on sheets of plastic and exposing them to light on an emulsion screen, then silkscreening them as assemblies. This is only one of the series.

And, like many things in my life, it speaks to history. I lean back in time, when I am working on a project. I go back. I look for, and at, history to build the base of content.

The tree, as a symbol and metaphor, is wide and deeply rich. So I gathered up some of these, redrawing illustrations that I’d found, working in live sketches, then reducing them — scratching and distressing them on the plastic surfaces that I’d worked with — using sandpaper. And then handscreened them full size.

One panel, from the island studio. There are 3 more, in other places:

Here are some snippets from the larger field of the imagery and history that I’d examined.

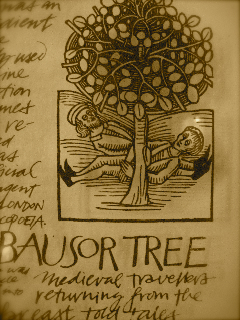

The Bausor dream tree, from a medieval drawing:

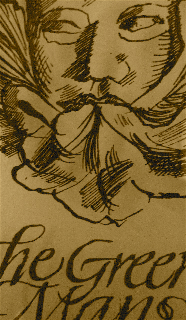

The Green Man, a pagan Christian spirit:

The Cork Oak, symbolizing rebirth:

Redrawn Victorian tree alphabet, from the 1800s

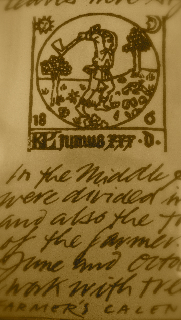

Juniper, discovered as a medicinal, later a gin ingredient:

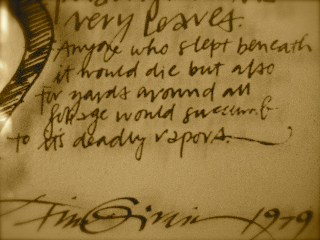

The Amber tree, a medieval stone maker:

A medieval forester, 1490, chopping wood:

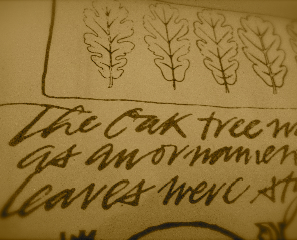

The Oak leaf as an ornamental device:

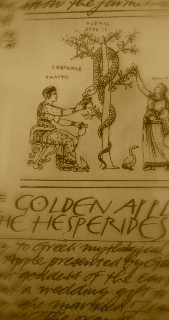

The Hespirides, the Golden Apple tree:

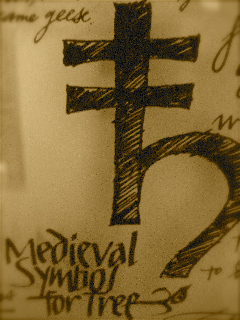

The medieval symbol for tree:

German oak tree crest for gymnastic association, 1920:

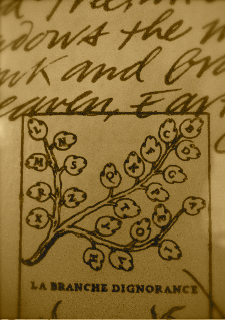

Branches of the alphabet, 1600s:

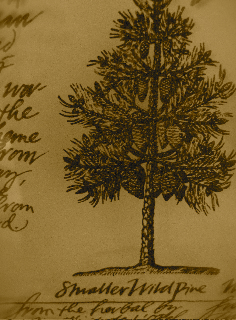

Pine engravings, redrawn, 15th century botanical:

Assyrian Life Tree, from an illustration 1800s:

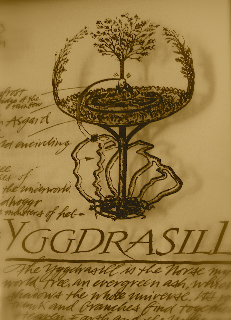

The Yggdrasill, the Norse Tree of the World:

This was a beginning for me — a starting point. Sharing of the love of trees with my father. That concretized my connection — with him, with me — in the love of trees. Trees as mystery, as maps of the world, as medicine, ingredients, myths, life givers and sources of inspiration. To this day, I still find myself looking at them, marveling.

This is the first of ten.

Tim Girvin | Decatur Island

Most of the transplanted trees at the family farm arboretum are local indigenous, but the cherished one is the tamarack that Matthew brought from Mongolia in his luggage on a return visit in 1999. It is now about 5 feet tall and carefully barricaded from the marauding deer and porcupine. Tamarack is the predominant conifer Mongolia. Matt would be very proud of this achievement.